Every Vote Matters

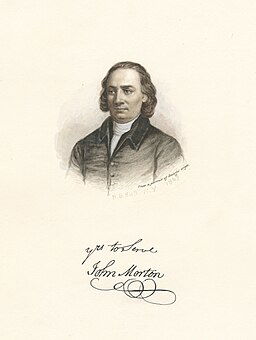

In Honor of John Morton

Native of Ridley Township

Delco’s Declaration of Independence Signer

In nearly every election of recent note, Pennsylvania is considered a “battleground state” or a “swing state,” meaning that it is one of the states that often determines the outcome of important national elections.

It is a role that our Commonwealth has held since the very beginning. Consider, for example, the vote to declare independence from the British Empire in the summer of 1776.

Tensions between Great Britain and her American colonies had been growing for a decade – since the passage of the Stamp Act in 1765. Open conflict erupted between the British Army and state militiamen in Massachusetts in April 1775. When representatives of the 13 colonies met in Philadelphia for the Second Continental Congress in May 1775, there was one important question: was it time to declare independence?

Delaware County’s John Morton was one of the delegates from Ridley Park, Pennsylvania who faced this difficult decision. There was uncertainty.

At the First Continental Congress in 1774, Morton could see both sides of this difficult question. Initially, favoring the path of reconciliation with Great Britain, fearing a “horrid contest” that would pit “Parents against Children and Children against parents.” Pennsylvania’s delegation to the Second Continental Congress in 1775 faced similar divisions over this momentous question. While delegate Benjamin Franklin favored independence, other members did not. In addition to Morton, John Dickinson, James Wilson and Robert Morris, all were against declaring independence.

On June 7, 1776, Virginia’s Richard Lee formally presented the plan to declare independence. Debate and a vote on this motion were set to begin on July 1st.

At this point, the colonial governments of the 13 colonies did not share in the growing enthusiasm for independence. Our founding fathers wanted the Declaration of Independence to be a unanimous declaration of the 13 colonies to stand unified in their struggle against the British Empire. Each colony had one vote, so 13 “yes” votes were needed to make it unanimous.

When debate began, unanimous approval was very much in doubt. Nine states were in favor. New York abstained from the vote because its state legislature was fleeing the British Army and could not provide guidance to its delegates in Philadelphia. Delaware’s two delegates were evenly split, and South Carolina and Pennsylvania were still voting no.

Between July 1 and 2, 1776, after hours of political discourse and dialogue, on July 2, 1776, they voted again, and the remaining pieces fell into place. South Carolina reversed course. Delaware’s Caesar Rodney rode through the night to arrive at the State House to break the Delaware delegation’s tie in favor of independence.

That left Pennsylvania as the lone holdout. If Pennsylvania voted no, the motion to declare independence would have carried, but not unanimously.

A unanimous decision held symbolic importance, as a unified decision of all Americans. Pennsylvania was a critical vote in making the Declaration of Independence unanimous.

Thomas Mifflin left Congress before the debate and final vote on July 2. Thomas FitzSimons and Jared Ingersoll voted against. John Dickinson and Robert Morris, both opponents of independence, abstained. James Wilson switched, joining Benjamin Franklin and George Clymer in favor of independence; leaving John Morton as the “swing vote” that would determine whether Pennsylvania voted yes on independence.

Despite his reservations, John Morton voted yes.

In an event that still reverberates through the world today, the 13 colonies unanimously declared their independence on July 2nd, 1776. The final document was approved and published on July 4th, 1776.

On July 8, 1776, the Declaration of Independence was first read publicly in Delaware County, at the 1724 Courthouse in Chester.

In August, John Morton returned to Independence Hall (then known as the Pennsylvania State House), to place his signature on one of our most important founding documents.

Sadly, Morton died less than a year after his vote in favor of independence at age 51, but the legacy of his courageous vote remains. During all these years, Anne Justis Morton, his wife, was caring for their estate and raising their nine children. In September 1777, after the Battle of Brandywine, the British Army were passing through the Ridley countryside and damaged the Morton property. Anne had to flee across the Delaware River with what valuables she could take to Billingsport, New Jersey. Many of John Morton’s papers were destroyed to protect the identity of their rebel, patriot friends, which could have broadened our understanding of his private and public life.

Every vote has power. Each time an American casts a vote, we honor 250 years of those who fought to secure the right to vote; starting with John Morton, Delaware County’s only signer of the Declaration of Independence.

Contributed by Michael Karpyn. Social Studies Teacher, Marple Newtown High School. Edited by Andrea Silva. For more information on John Morton, listen here or read his biography here.